Speech delivered by Morena Luciani Russo in occasion of the international meeting “LE RADICI MATERNE DEL DONO”, published by Vanda Ed. 2016.

Those who have never seen a church adore ovens.

Sardinian saying

From a spiritual point of view, it seems both most urgent and vital to approach the question of gift giving. Latest research attests to the fact that matriarchal societies tend to be characterized by a gift economy, and an equal distribution of goods. Such societies also adopt an attitude of profound spirituality permeating every single aspect of daily life, a spirituality oriented towards the earth and the cycles of nature, and based upon the insight that women are sacred (Heide Goettner-Abendroth 2012).

From my own point of view, both as a researcher and a Shaman, I consider the giving of gifts to be at the very core and center of Female Shamanism. We should retrieve this concept. It might permit us to grasp the essence that inspired these expressions of female identity. For far too long, they have found little or no voice within male dominated research, be it anthropological or religious. This kind of research has always embraced an idea of Shamanism tuned down to the male and the neutral, which has little or nothing to share with its original meanings [1].

We might say that the male perspective on Shamanism has always been focused upon the presumed fantastic powers of the Shaman, on a personality that is both egocentric and eccentric, upon its social and political implications, and, as far as the present is concerned, a path of healing perceived as personal, individual growth.

If considered at all, women in this perspective often figure as healers, or else as able craftswomen. Otherwise, they are just seen as bitches, witches, bewitching and obsessed. But let me rather dwell on the “positive” aspects. We need them desperately!

But what has often been classified as mere “handcraft”, excluding any artistic merit, being deeply embedded within the necessities of daily life, expresses the matriarchal vision of the cycles of life, where the sacred dimension and daily life are intrinsically blended into one another.

Sowing, embroidery, the decoration of objects and domestic walls, or previously of caves, the preparation of food, as well as the weaving of baskets, all testify to transformation processes that women all over the world were able to perform with their hands and body, assuming even greater ritual significance during certain moments of passage – childbirth, becoming an adult, death, marriage and other moments of the sacred annual calendar.

Anthropologists have repeatedly discussed the significance and meaning of such rituals, but as so often, our western approach derives from a fractured understanding. Some have pointed out the social function of rituals, others their religious implications, or else the religious implications as a premise for social functions and a means to reinforce these within a given community. Others yet, to cite De Martino as an example, recognize ritual as the human response to the overwhelming mystery and might of nature, but in the sense of an impelling urge to control and overcome that nature.

As I said, these are male and very patriarchal points of view. It is my impression that almost nobody ever questioned themselves about ritual ceremonies performed by women, about what women actually do on such occasions. First of all, women basically bring offerings. But throughout thousands of years of patriarchy, men assumed spiritual and political leadership, and the true sense of this aspect was utterly lost. Offering remained, so to speak, marginal, and confined to the outskirts of other ritual functions that, in some cases, took on a heightened performance character. Now offerings are clearly gifts. But gift giving, offering and ritual will not be understood as long as we adopt linearity as our point of view. Native and rural cultures have to some extent maintained a cyclic concept of nature, and thus preserved the original significance of ritual as a gift.

From the point of view of female Shamanism, rituals are actions aimed at reestablishing balance between all the different levels of existence, be they physical, psychophysical, social, political or spiritual. Flavio Pinto, scholar of ancient writing and friend, once pointed out to me that if we go back beyond Latin and Greek etymology to Sanskrit as the old Indo-European language, we can make interesting discoveries regarding the significance of certain terms.

So I focused my attention on the root rta contained within the modern term “ritual”, and that root has a number of meanings that seem most interesting to me in this context, such as “health”, “sacred act”, “rule”, “honored” and “respected”.

Rituals set out to create “order”, and this very same term “order” comprises, through its similarity in sound, the word for “gift”, which in Sanskrit is dana or dhana, meaning “valued”, “treasured”, “cherished”, and “offering”. Through ritual, we offer something precious, so that we can say that rituals are based on the giving of gifts.

But yet one further consideration has to be made. In western eyes, this kind of gift has strictly utilitarian connotations, and has been reduced to the idea of exchange. Rituals would seem to be performed merely as a means to obtain some given result, in order to get what we want. And in fact we do receive something from any ritual, but this is not the point. Rituals are not about exchange. From a cyclic, matriarchal point of view, rituals are first of all gifts, thanksgiving, and celebration.

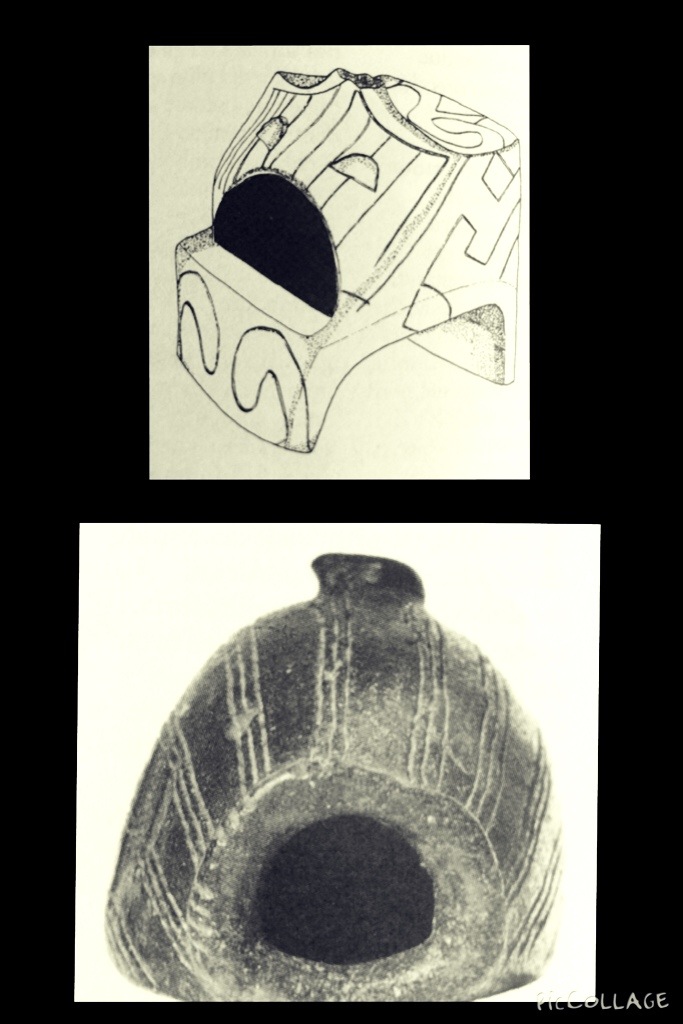

Women have always used their creative and spiritual powers to fashion special gifts for the Mother of the Universe and Life, and celebrate the cycles of nature. Amongst these special gifts, outstanding examples are provided by ritual bread making as practiced throughout Europe and the Mediterranean. Bread has always been at the very core and center of female ceremonies since the Neolithic age. Marija Gimbutas (2008) evidences bread ovens present in many Goddess sanctuaries of ancient Europe. Loafs were often shaped to resemble body parts of the Goddess of Life, such as buttocks, vulva and breasts, and were decorated with the ancient symbols of life and regeneration, as we can see from the images published by Gimbutas. The very same ovens in which bread was baked were often shaped to resemble the female body, featuring eyes and mouth, and in some cases the pregnant womb, complete with a protuberance recalling the umbilical cord.

As Kathy Jones (2013) points out, bread represented the sacred transformation of the life-bestowing Goddess of Grain, the Mother of Life, and thus figured within her sanctuaries.

The Sanskrit root pan evidences, amongst other meanings, concepts of “honor” and “being worthy of admiration”, so that we can say that that which sustains life is to be cherished, admired and honored, being the very essence of gift giving; and this is one of the reasons why bread has always received special attention.

It is well known that the ancient cyclic concept of nature, featuring spring as a young girl in flower, harvest as a mother, and winter and regeneration as an old woman, was taken up by Greek culture, where it found its expression in the myth of Persephone, Demeter and Hekate, and that ritual bread making was an integral part of the Mysteries of Eleusis, which were held in their honor each autumn.

And I mention Demeter and Persephone since my studies brought my attention to certain rites that are still practiced throughout present day Italy, and which are probably connected to this ancient divine cosmic couple. Let me tell you how women prepare and conduct these sacred events, for they are most apt to render an idea of how the spirituality of gift giving can act within a given community.

The first of these occasions is celebrated at Goriano Sicoli, in Abruzzo. It is a very ancient ceremony, which was later associated with the Christian veneration of Santa Gemma, and features a young girl and her commare, which in dialect refers to a mature, grown woman. It is held thrice every year, the prime celebration during May, in springtime, documented by the precious study of Paola Di Giannantonio.

Celebrations are conducted by a different couple of young spouses each year. The couple remains in charge of preparations that continue throughout the entire year, and involve the entire community. Originally, this also implied a redistribution of riches, since normally some less advantaged family would be chosen, thus providing its members with the necessary goods to outbalance any economic disproportion.

The couple, referred to as the procuratore and the procuratrice, literally the “providers”, are given the keys of the House of Santa Gemma, a sacred place, where bread is prepared, and all that is necessary for the ceremony is collected. The procuratrice and the procuratore share the tasks of collecting grain, grapes, eggs and money contributions and so forth. What is absolutely striking is that each and every family contributes according to their own possibilities, the grain provided by all being collected and preserved together with the grapes, which end up together in the casks to produce wine.

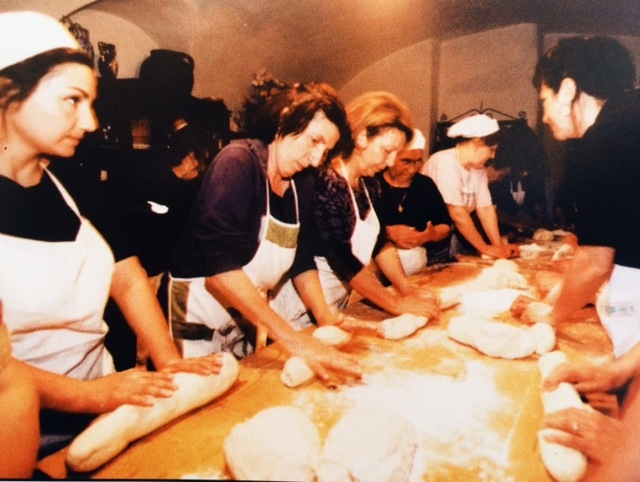

Women meet on the night of April 30th.[2] to prepare the loafs in the House of Santa Gemma. The procuratrice precedes them, and lights the fire which she must kindle and keep burning throughout the three days and nights of ritual preparation to come. It should be pointed out that being in charge of the fire has always constituted a typical element of female Shamanism.

Bread making starts refreshing the “mother”, or natural yeast. In past times, this was obtained uniting the yeast provided by each single family. Women work on a single long table, kneading the dough, and passing each loaf on, one at a time, so that each single loaf will have been touched by each single woman. Loafs are decorated with three parallel slits and the initials of Santa Gemma (S and G). Afterwards, the women used to bake the loafs at home, and then bring them back to the House, but nowadays this task is executed by the men, even if they are not allowed to enter the House during the rite, and wait at the entrance for the women to pass them the loafs to bake.

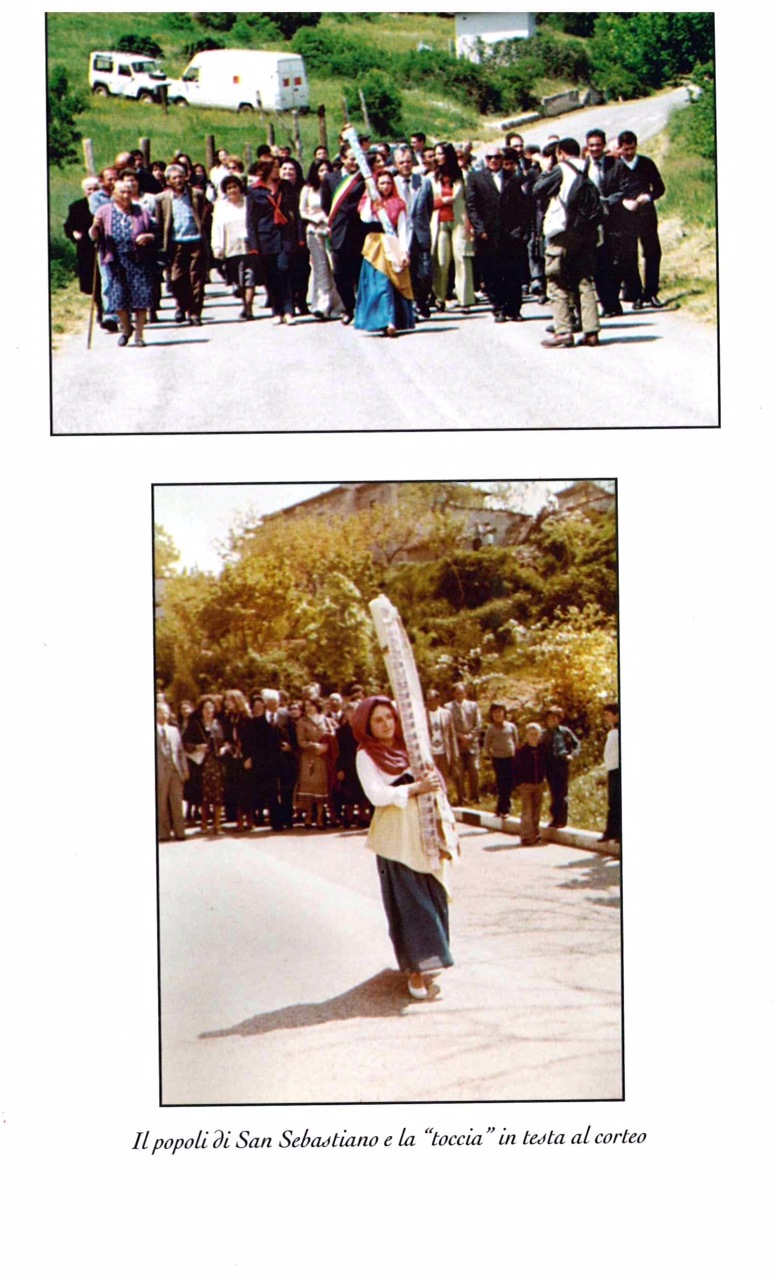

Women take turns, but in some cases may work without interruption for three days and three nights. Once the bread has been baked, it is brought into a single room of the House, and placed there according to a set rule. And here it will remain until May 11th., when the day of the celebration that all have been looking forward to comes, and when the mothers poise ritually decorated baskets onto the heads of their daughters, and fill them with the loafs. It is an ancient custom that the girls should not be admitted to the room of the bread. They are to distribute the sacred loafs amongst the whole community, and to guests.

The bread does not decay, it is devoutly kissed when received, preserved at home, and consumed throughout the year. The highlight of the ceremony is reached when the girl incarnating the saint, walking to the village from a nearby community, and bearing a thick candle, joins her commare in the House. What else can come to mind but the very myth of Demeter joining Persephone!

But let us move on farther down south, into Campania, to Castelvetere sul Calore, in the province of Avellino. There, on April 28th, the Madonna delle Grazie is celebrated. For three weeks, the women of the entire village knead and bake loaves shaped like little doughnuts, referred to as tortano.

These doughnuts are piled up to form an immense altar dedicated to the Madonna: an average of almost 45.000 tortani placed one on top of each other, composing an immense and imposing structure.

Bread is kneaded rhythmically by groups of women in large wooden bowls, in a dance-like movement; flour is donated by each single family, and throughout the whole preparation, the nutrici, or “nurturesses”, continue to lead the singing (just consider how much energy flows into these loaves!). When the day of bread making arrives, on April 25th, all the women wash their hands and face with the same water, and in the same bowl.

But center-stage of this ceremony is held by the young girls who figure as dispensatrici, literally “distributors” As we were able to see before, it is their task to distribute bread to the entire community on that special day.

During the days that precede celebrations, the families of the dispensatrici collect gold from their families and friends, such as bracelets, necklaces and earrings, signing down each item, so that they may be duly returned after the ceremony; all this jewelry is sown into the dresses of the young girls, into a kind of corset. Personally, I consider this custom a beautiful manner of investing young girls with the task of conveying the notion of the sacred, endowing them with the power to bring blessings to the entire community. It reminds me of the ”forgotten” child goddess described by Mario Bolognese[3].

The tortano is sacred and protective. It is consumed, or else displayed at home, in public spaces, or recently even hung up in cars.

We find instances of ritual bread making throughout all of Southern Italy, in Puglia as in Sicily. But I would like to dedicate my conclusion to a most special custom to be found in Sardinia.

This custom has been amply and extensively catalogued (various authors 2005). Take a glance at these two women in splendid ceremonial attire, ready to prepare bread loaves decorated with bird and nature images. In Sardinia as well, bread was prepared, decorated and baked by women.

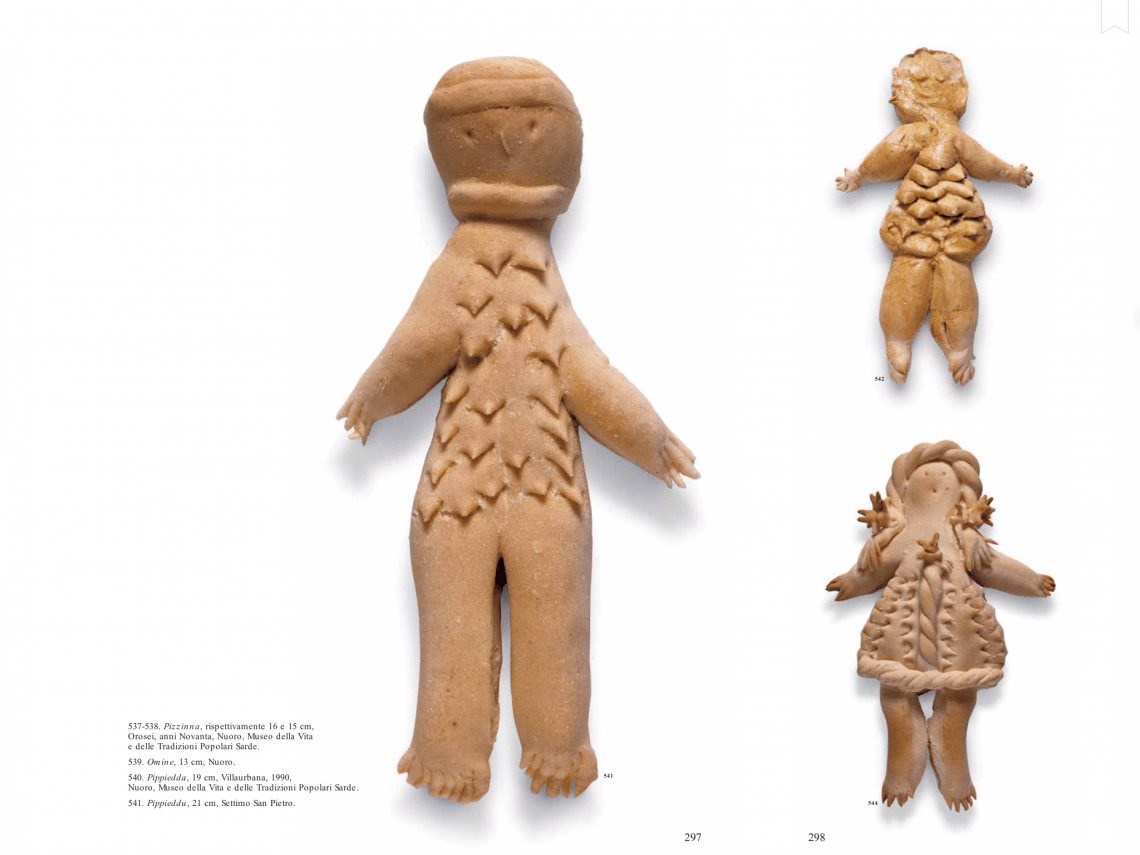

On this island, ritual bread is highly important, to the extent of being considered the essence of all the arts. In fact there are a number of varieties for all occasions, bread to commemorate the dead, bread to celebrate marriage, and bread used for magic as well, and even toy bread for children.

Amongst the more elaborate forms of bread we find the loaves named Sa Coccoi, which the women from the community of Lei, literally “She”, in the Nuoro province, prepare in small groups between April 24th and April 25th. These are offered celebrating Saint Mark in a small nature sanctuary. They sometimes display a small perforation in the center, or else are offered in little baskets. These are replenished with the manifestations of life, with bird nests, flowers, leaves and fruit. Some of them are placed on top of each other, decorated with paper and ribbons, and the women parade them about on sticks during the procession.

There is also the custom of fashioning loaves that are quite explicitly shaped like a vulva, and can be given by a spouse to her husband to come, denominated Is Pillosas.

A highly enlightening study by Salvatore Dedòla (2008) reveals the extent to which Sardinia has retained its roots within an ancient cultural background that preceded the arrival of Indo-Europeans, while Latin influence has remained rather superficial; according to this linguist, Pillosa would seem to derive from the ancient Pell-usu, meaning “goose egg”. I consider this to be a reminder of the egg that created the universe, symbol of the Mother of Life, mentioned by Marija Gimbutas, and which finds its mirror image in the vulva.

Other loaves are breast-shaped, and there is one version depicting a woman with a multitude of breasts, recalling the Artemis of Ephesos; such loaves were given to little girls (Dedòla 2008).

If we want to remain within the realm of the celebration of life, we should not forget that in Sardinia, the bride also receives her loaf of bread, which in this case assumes a phallic form, and should be consumed on the very day of marriage.

Amongst this variety of ritual forms created by women there is another important bread loaf named Pippia de Caresima, a kind of calendar girl child, a leg of which is consumed for each of the weeks that precede Easter.

Dedòla further brings our attention to a perforated loaf, a kind of elliptical doughnut named Sa Forrottula, the name of which would derive from the ancient form Burrutu, with the addition of the Sardinian adjective la, meaning “female servants of the sanctuary”: it would seem that this was the bread of the priestesses performing sacred prostitution; and that throughout Sardinia, there were at least 17 sacred sites dedicated to this custom. Sacred prostitution or sacred sexuality? We cannot hope to approach this subject here. But let it be said that when we use the term “prostitution”, we are very likely to fall back into our own modern mental categories, and apply them to ancient cultures.

As last instance of ritual gift, I would like to share this incredible composition created by the women of Fonni, in the province of Nuoro, in occasion of the celebration of San Giovanni, on June 24th. It is called Cocone e’ Frores, meaning “sweet [5] and shaped like an elevated sanctuary and baked in the oven”.

It is a structure six to seven meters high, composed of about 250 pigeons and chicken, carried through the streets in occasion of the procession of San Giovanni, and consumed and shared towards the end of August.

All this is but to show you how much time and energy women invest in ritual art. Bread making is just one case. We could cite numerous other examples from all over the world to show how the creative implications of ritual gift giving can empower women, and enable them to continue to experience the dimension of Shamanism, and offer it to a new society.

VIEW THE ENTIRE CONFERENCE. From minute 40:00, the section dedicated to spirituality by Morena Luciani Russo, Vicki Noble, Letecia Layson and Camilla

Bibliography

Various Authors (2005), Pani. Tradizione e Prospettive della Panificazione in Sardegna, Ilisso Edizioni.

Dedòla S. (2008), I Pani della Sardegna, Grafica del Parteolla.

Di Giannantonio P. (2005), Demetra per sempre. La festa delle donne a Goriano Sicoli. Culti alternativi agrari nella Valle Subequana e nella Valle Peligna, Margaret Fuller Edizioni.

Gimbutas M. (2008), Il linguaggio della Dea, Venexia.

Goettner-Abendroth H. (2012), Le società matriarcali. Studi sulle culture indigene del mondo, Venexia.

Jones K. (2013), La Dea nell’antica Britannia, Psiche 2.

Luciani M. (2012), Donne sciamane, Venexia.

[1] For an in-depth discussion of this question, see Donne sciamane(2012).

[2] It should be pointed out that this is a sacred night of the ancient calendar, the night that ushers in the first of May.

[3] Mario Bolognese, writer, poet and educator, is specialized in Gylanic education. His books evidence the importance of the girl as a goddess, which has been swiped out by patriarchy.

[5] Dolce, in this case, sweet bread.